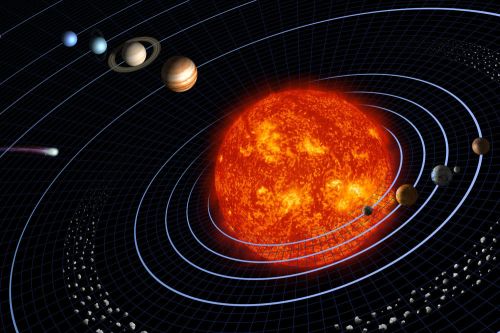

Birth of the sun

A massive concentration of interstellar gas and dust created a molecular cloud that would form the sun’s birthplace. Cold temperatures caused the gas to clump together, growing steadily denser. The densest parts of the cloud began to collapse under its own gravity, forming a wealth of young stellar objects known as protostars. Gravity continued to collapse the material onto the infant object, creating a star and a disk of material from which the planets would form. When fusion kicked in, the star began to blast a stellar wind that helped clear out the debris and stopped it from falling inward.

Although gas and dust shroud young stars in visible wavelengths, infrared telescopes have probed many of the Milky Way Galaxy’s clouds to reveal the natal environment of other stars. Scientists have applied what they’ve seen in other systems to our own star.

After the sun formed, a massive disk of material surrounded it for around 100 million years. That may sound like more than enough time for the planets to form, but in astronomical terms, it’s an eye blink. As the newborn sun heated the disk, gas evaporated quickly, giving the newborn planets and moons only a short amount of time to scoop it up.

Formation models

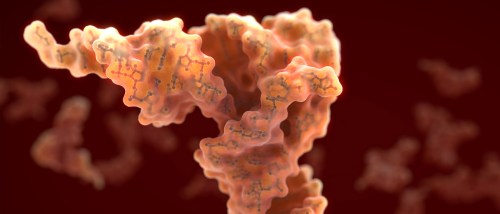

Scientists have developed three different models to explain how planets in and out of the solar system may have formed. The first and most widely accepted model, core accretion, works well with the formation of the rocky terrestrial planets but has problems with giant planets. The second, pebble accretion, could allow planets to quickly form from the tiniest materials. The third, the disk instability method, may account for the creation of giant planets.

The core accretion model

Approximately 4.6 billion years ago, the solar system was a cloud of dust and gas known as a solar nebula. Gravity collapsed the material in on itself as it began to spin, forming the sun in the center of the nebula.

With the rise of the sun, the remaining material began to clump together. Small particles drew together, bound by the force of gravity, into larger particles. The solar wind swept away lighter elements, such as hydrogen and helium, from the closer regions, leaving only heavy, rocky materials to create terrestrial worlds. But farther away, the solar winds had less impact on lighter elements, allowing them to coalesce into gas giants. In this way, asteroids, comets, planets and moons were created.

Some exoplanet observations seem to confirm core accretion as the dominant formation process. Stars with more “metals” — a term astronomers use for elements other than hydrogen and helium — in their cores have more giant planets than their metal-poor cousins. According to NASA, core accretion suggests that small, rocky worlds should be more common than the more massive gas giants.

The 2005 discovery of a giant planet with a massive core orbiting the sun-like star HD 149026 is an example of an exoplanet that helped strengthen the case for core accretion.

“This is a confirmation of the core accretion theory for planet formation and evidence that planets of this kind should exist in abundance,” said Greg Henry in a press release. Henry, an astronomer at Tennessee State University, Nashville, detected the dimming of the star.

In 2017, the European Space Agency plans to launch the CHaracterising ExOPlanet Satellite (CHEOPS), which will study exoplanets ranging in sizes from super-Earths to Neptune. Studying these distant worlds may help determine how planets in the solar system formed.

“In the core accretion scenario, the core of a planet must reach a critical mass before it is able to accrete gas in a runaway fashion,” said the CHEOPS team. “This critical mass depends upon many physical variables, among the most important of which is the rate of planetesimals accretion.”

By studying how growing planets accrete material, CHEOPS will provide insight into how worlds grow.

The disk instability model

But the need for a rapid formation for the giant gas planets is one of the problems of core accretion. According to models, the process takes several million years, longer than the light gases were available in the early solar system. At the same time, the core accretion model faces a migration issue, as the baby planets are likely to spiral into the sun in a short amount of time.

“Giant planets form really fast, in a few million years,” Kevin Walsh, a researcher at the Southwest Research Institute (SwRI) in Boulder, Colorado, told Space.com. “That creates a time limit because the gas disk around the sun only lasts 4 to 5 million years.”

According to a relatively new theory, disk instability, clumps of dust and gas are bound together early in the life of the solar system. Over time, these clumps slowly compact into a giant planet. These planets can form faster than their core accretion rivals, sometimes in as little as 1,000 years, allowing them to trap the rapidly vanishing lighter gases. They also quickly reach an orbit-stabilizing mass that keeps them from death-marching into the sun.

As scientists continue to study planets inside of the solar system, as well as around other stars, they will better understand how gas giants formed.

Pebble accretion

The biggest challenge to core accretion is time — building massive gas giants fast enough to grab the lighter components of their atmosphere. Recent research probed how smaller, pebble-sized objects fused together to build giant planets up to 1,000 times faster than earlier studies.

“This is the first model that we know about that you start out with a pretty simple structure for the solar nebula from which planets form, and end up with the giant-planet system that we see,” study lead author Harold Levison, an astronomer at SwRI, told Space.com in 2015.

In 2012, researchers Michiel Lambrechts and Anders Johansen of Lund University in Sweden proposed that tiny pebbles, once written off, held the key to rapidly building giant planets.

“They showed that the leftover pebbles from this formation process, which previously were thought to be unimportant, could actually be a huge solution to the planet-forming problem,” Levison said.

Levison and his team built on that research to model more precisely how the tiny pebbles could form planets seen in the galaxy today. While previous simulations, both large and medium-sized objects consumed their pebble-sized cousins at a relatively constant rate, Levison’s simulations suggest that the larger objects acted more like bullies, snatching away pebbles from the mid-sized masses to grow at a far faster rate.

“The larger objects now tend to scatter the smaller ones more than the smaller ones scatter them back, so the smaller ones end up getting scattered out of the pebble disk,” study co-author Katherine Kretke, also from SwRI, told Space.com. “The bigger guy basically bullies the smaller one so they can eat all the pebbles themselves, and they can continue to grow up to form the cores of the giant planets.”

A Nice model

Originally, scientists thought that planets formed in the same part of the solar system they reside in today. The discovery of exoplanets shook things up, revealing that at least some of the most massive objects could migrate.

In 2005, a trio of papers published in the journal Nature proposed that the giant planets were bound in near-circular orbits much more compact than they are today. A large disk of rocks and ices surrounded them, stretching out to about 35 times the Earth-sun distance, just beyond Neptune’s present orbit. They called this the Nice model, after the city in France where they first discussed it.

As the planets interacted with the smaller bodies, they scattered most of them toward the sun. The process caused them to trade energy with the objects, sending the Saturn, Neptune, and Uranus farther out into the solar system. Eventually the small objects reached Jupiter, which sent them flying to the edge of the solar system or completely out of it.

Movement between Jupiter and Saturn drove Uranus and Neptune into even more eccentric orbits, sending the pair through the remaining disk of ices. Some of the material was flung inward, where it crashed into the terrestrial planets during the Late Heavy Bombardment. Other material was hurled outward, creating the Kuiper Belt.

As they moved slowly outward, Neptune and Uranus traded places. Eventually, interactions with the remaining debris caused the pair to settle into more circular paths as they reached their current distance from the sun.

Along the way, it’s possible that one or even two other giant planets were kicked out of the system. Astronomer David Nesvorny of SwRI has modeled the early solar system in search of clues that could lead toward understanding its early history.

“In the early days, the solar system was very different, with many more planets, perhaps as massive as Neptune, forming and being scattered to different places,” Nesvorny told Space.com

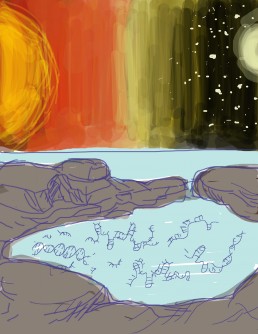

Water gatherers

The solar system didn’t wrap up its formation process after the planets formed. Earth stands out from the planets because of its high water content, which many scientists suspect contributed to the evolution of life. But the planet’s current location was too warm for it to collect water in the early solar system, suggesting that the life-giving liquid may have been delivered after it was grown.

But scientists still don’t know the source of that water. Originally, they suspected comets, but several missions, including six that flew by Halley’s comet in the 1980s and the more recent European Space Agency’s Rosetta satellite, revealed that the composition of the icy material from the outskirts of the solar system didn’t quite match Earth’s.

The asteroid belt makes another potential source of water. Several meteorites have shown evidence of alteration, changes made early in their lifetimes that hint that water in some form interacted with their surface. Impacts from meteorites could be another source of water for the planet.

Recently, some scientists have challenged the notion that the early Earth was too hot to collect water. They argue that, if the planet formed fast enough, it could have collected the necessary water from the icy grains before they evaporated.

While Earth held onto its water, Venus and Mars would have likely been exposed to the important liquid in much the same way. Rising temperatures on Venus and an evaporating atmosphere on Mars kept them from retaining their water, however, resulting in the dry planets we know today.