Moving Backward to Go Forward

DNA, RNA, and protein: these have been the premier scientific buzzwords in our lives since we picked up our first science textbooks in elementary school. However, there was always one thing that the science textbook never really got around to explaining: what came first the chicken or the egg? Or in our case, RNA or protein?

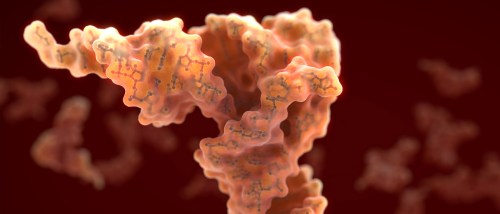

Scientists at The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) have taken steps to answer the long-standing question to verify the validity of the RNA world hypothesis. The Museum of Science explains that according to the RNA World Hypothesis, “earlier forms of life may have relied solely on RNA to store genetic information and to catalyze chemical reactions. Later life evolved to use DNA and proteins due to RNA’s relative instability and poorer catalytic properties, and gradually, ribozymes became increasingly phased out.”

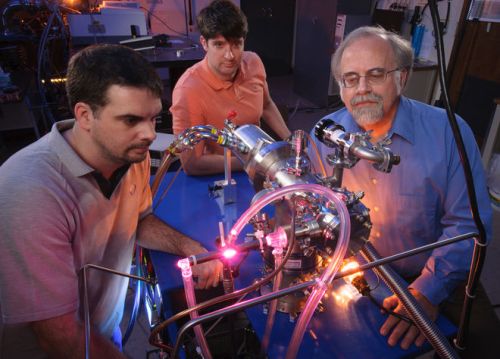

In short, to test this, the team has decided to build their own biological time machine to take them back 4 billion years—all by synthesizing a primordial RNA-based enzyme, a ribozyme, that has never been seen before.

The team of scientist sought to verify the two major tenets of the RNA world hypothesis:

- The ribozyme must be able to replicate RNA.

- The ribozyme must be able to transcribe RNA.

Here is a brief video describing both replication and transcription from a DNA perspective:

A Primordial Hunger Games

The scientists employed natural selection in their process to uncover evidence for the RNA world hypothesis. Building upon decades of research, the researchers made over 100 trillion variants of the class I RNA polymerase ribozyme, a molecule that theoretically could replicate and transcribe RNA.

After twenty-four rounds of experiments, the TSRI team stumbled upon polymerase ribozyme 24-3, which was able to replicate and transcribe RNA better than the team had hoped. With the new molecule synthesizing RNA molecules at a rate that is one hundred times quicker than the original start molecule, and replicating at a rate deemed as exponential replication, with forty thousand copies produced in just 24 hours.

The scientists believe that “a polymerase ribozyme that achieves exponential amplification of itself will meet the criteria for being alive.” Providing support for the RNA world hypothesis.

Now that’s one for both history and science textbooks.

The article was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences